During the introduction, with sunshine pouring through the dome at the centre of the hall, we were reminded that the Sacred Space offers "a welcome to Canadians of every religious background", which is good, because Canadians for every religious background have been honoured here. There's a large boulder, a Sacred Stone, so to speak, in the centre of the hall, around which a dozen people walked at its inauguration, each one representing a different faith; this must have been an extraordinary moment.

The singer and pianist thereafter took turns to come to the lectern and talk about the music they were about to perform. Each section of the programme was headed by the name of a different part of the world (England, Germany, France, North America) from which 1st World War soldiers had come.

George Butterworth, a British Lieutenant killed in the Battle of the Somme, had been a promising composer, and is particularly well remembered for the Six Songs from A Shropshire Lad (Housman's poems) that he wrote before going off to war. Since I know these songs note-for-note, I was interested in their interpretation and impressed by the lovely soft start to Loveliest of Trees and Is My Team Ploughing? --- the first and last songs in the cycle. Mr. Brancy took the famous one about The Lads In Their Hundreds at a slow tempo that my husband would find challenging, because of the amount of breath required for each phrase. Brancy was very good at articulation, making the most of the consonants ("the horses trrrrample ...") and putting expressive crescendos / decrescendos on the long vowels (as in "easy" or "sweetheart").

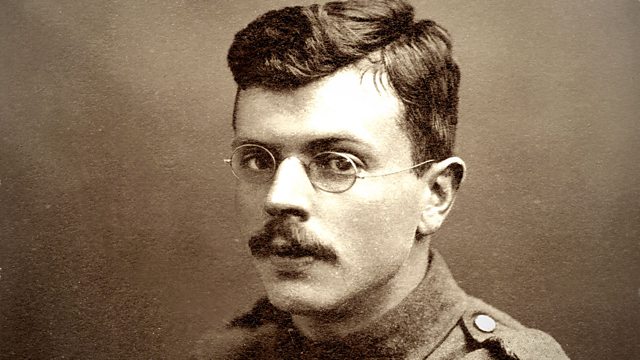

|

| Ivor Gurney |

France. Since reading Michel Bernard's novel, Les Forêts de Ravel, I knew that Maurice Ravel, in his 40s, had served as an ambulance driver on the battlefields of the 1st World War, and had composed Le Tombeau de Couperin at this time. We heard the Prélude and Toccata from this suite, each movement of which was composed in memory of a fallen friend, as well as Ravel's song Trois Beaux Oiseaux du Paradis, about imaginary birds carrying a last message to the loved ones of three men who have died in the trenches.

The performers tried to relieve our sombre state of mind by making a little joke about Ravel's Toccata: "That was a lot of notes for a small piano."

I had not known that the composer Francis Poulenc had also served in that war, in fact in both world wars. One of the songs we heard by him was the setting of a poem by Apollinaire, entitled Bleuet, meaning cornflower, which was a nickname for the French soldiers in their blue hats. The other song was aptly entitled Priez pour Paix. Here is John Brancy singing it in November 2014, with Peter Dugan accompanying:

Debussy did not directly take part in the war, being too old, but wrote a fast and angry song which was a setting of his own words, called Noel des enfants qui n'ont plus de maisons: Christmas for the children who no longer have homes.

The music of Charles Ives from the USA didn't lighten the audience's mood either with their rendition of three war songs by Charles Ives (1874-1954), written during the month America entered the 1st World War. One of them was a setting of McCrae's In Flanders Fields, the war poem best known to Canadians, that's recited here every November 11th.

The final section of the concert was a performance of four of the popular songs of those days, which the ordinary English-speaking soldiers would have known and sung along to: Keep the Home Fires Burning, My Buddy, God Be With Our Boys Tonight and Danny Boy. What was novel about this was that the pianist, Peter Dugan, had composed his own accompaniment for these songs, so that we heard echoes of pianistic gunfire in the background, evocative indeed. Like the rest of the songs on the programme, they were very well sung by John Brancy.

This was a concert that gave rise to many thoughts, so that I wanted to be by myself for a while at the end of it, and slipped away rather than stay for the refreshments. A day or so later, I read the Hardy poem to my mother, who appreciated it. She'll be 98 this month, conceived at the end of the 1st World War.

_sq.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment