Chris was off work on Friday so we went out in the fresh air, into the Rockcliffe Park woods where I picked up some fallen white pine twigs to decorate our porch. I know they'll stay green till springtime.

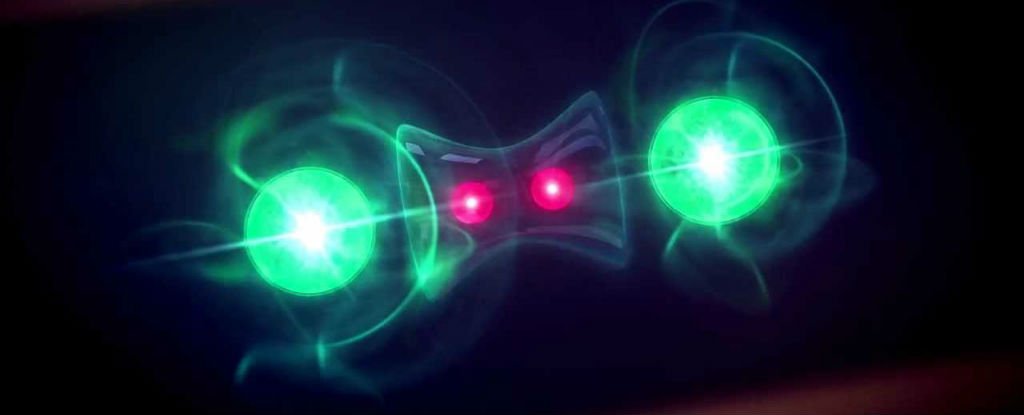

In the evening, we walked again, to a philosophers' gathering with Barbara, Drew, Letitia, Nicola and Andrew. By means of a miniature whiteboard and markers that he had bought at the Dollarama store, Andrew described an "experiment" involving a mysterious "machine" that was able to make unexplained connections between a push-button and two different receivers, far apart, turnig their green or red lights on according to their settings ... or perhaps not! If the settings were identical, the same-coloured lights came on after the button was pushed. If not, there was a 25% chance the same lights would come on, although logically this ought to have happened more often. Even though it was simply enough explained, with no long words, I couldn't follow the reasoning too well; it turned out to be about "quantum entanglement" and "spooky action at a distance". Andrew later sent us an email telling us where he had found the idea: in a paper published by the Journal of Philosphy called Quantum Mysteries for Anyone, by David Mermin. Chris was grinning throughout, able to follow the train of thought, and our son who studied this kind of thing at university and whose pulsar research is full of references to General Relativity, would have been at home with it, too, although Andrew seemed to be telling us that the laws of General Relativity were inadequate. The quantum particles (or waves ... Andrew said there was no such thing as a particle) have some means of communicating with one another at a speed faster than the speed of light, apparently. I thought (but didn't say) that it must be telepathy, then. Somebody said that if we could grasp what was happening, there'd be nothing to prevent us from time-travel. Chris drew parallels with the non-intuitive Banach-Tarski paradox (a mathematical proof that you could cut an imaginary solid ball into a number of pieces, maybe as few pieces as five, and then reassemble those pieces into two solid balls of the same original size) which sounds to me like something the Sorcerer's Apprentice did.

Before our group was thrown out of the cafe at closing time, the subject of the conversation had changed to the difference between right and wrong, whether we can know the difference without being conditioned to know, and the influence of trends and fashions on people's thinking. We walked half of the way home with Nicola, still mulling things over, of course, and Nicola urging me to resume work on a book he once saw me struggling to write. I finally managed to fall asleep around 1:30 on Saturday morning.

We met Elva, Laurie and Carol for lunch on Saturday, but I spent most of the day tidying up and preparing supper at our house for five other friends who stayed here till after midnight --- none of us realised so much time had gone by. I thought the evening was going to be a disaster as it began with a disaster: I forgot to open the vent in the fireplace before lighting the log fire and so greeted our five supper guests with clouds of smoke in the living room and the smoke detector beeping ear-piercingly. Everyone was forgiving though and Farhang even said that the smell reminded him happily of his childhood in an Iranian village, where the tandoor (تنور) in the centre of their house had often leaked smoke!

With apple juice and ginger ale instead of wine or beer to drink, we ate a vegetarian meal (cashew stir fry), because, for Farhang and Guitty, any meat would have had to be halal, and also because Judy and Dick are vegetarians, have been so for thirty years. Barbara told us that in Mongolia, where she'd been in August, meat was all there was to eat, mutton mostly, or horse-meat. She described a sort of Mongolian pressure cooker in which a stew was cooked by means of the fire-hot pebbles placed in it. The conversation grew gradually deeper and more animated, so that by the time we were sitting around the fire again (we ran out of fresh logs) we were onto manners, the aims of education and the origin of fashions (which would have tied in nicely with Friday's discussion), history ancient and modern, and the impossibility of a secular state. A.C. Grayling was mentioned, as was the Gilgamesh epic. I forget how that came up, Farhang saying that he revisits the story every year and loves it, telling me that if I wanted to write a version for children, as I confessed I did, he would help me with that project. He pronounced the name Enkidu as En-KEE-doo. We had no idea how late it was getting until one of us suddenly glanced at a watch that told us it was already 10 to midnight. Then they applauded me, in spite of the smoke-out, for being a nice hostess.

With apple juice and ginger ale instead of wine or beer to drink, we ate a vegetarian meal (cashew stir fry), because, for Farhang and Guitty, any meat would have had to be halal, and also because Judy and Dick are vegetarians, have been so for thirty years. Barbara told us that in Mongolia, where she'd been in August, meat was all there was to eat, mutton mostly, or horse-meat. She described a sort of Mongolian pressure cooker in which a stew was cooked by means of the fire-hot pebbles placed in it. The conversation grew gradually deeper and more animated, so that by the time we were sitting around the fire again (we ran out of fresh logs) we were onto manners, the aims of education and the origin of fashions (which would have tied in nicely with Friday's discussion), history ancient and modern, and the impossibility of a secular state. A.C. Grayling was mentioned, as was the Gilgamesh epic. I forget how that came up, Farhang saying that he revisits the story every year and loves it, telling me that if I wanted to write a version for children, as I confessed I did, he would help me with that project. He pronounced the name Enkidu as En-KEE-doo. We had no idea how late it was getting until one of us suddenly glanced at a watch that told us it was already 10 to midnight. Then they applauded me, in spite of the smoke-out, for being a nice hostess.That night I fell asleep more quickly.

For lunch on Sunday we met Nicola again, plus Maha, this time at the Scone Witch cafe on Beechwood, and made plans to visit them again at the end of December when their daughter would be home. Back at our house, on Sunday evening, we had Elva, Laurie, Carol and Don round, for a supper to which everyone contributed, Carol and Elva bringing meat pies, etc. Before they arrived I lay down in the dark in an attempt to snatch a moment's sleep, but hardly succeeded. Then I (carefully) lit another fire. Chris managed to resurrect some of the previous nights' conversations to some extent, but (with wine or beer on offer this time round) we were too relaxed to argue very much.

Finally, hot ashes in the fireplace now, a layer of snow all over the garden and a proper mess in the kitchen, then bed.