The longer we have to wait for a departure date for Hangzhou the more of the language I'll be able to learn first. That is the positive way to look at it, but the frustration over our lack of information is getting me down, rather, at the moment. I have to remember that it's not a holiday trip but a business trip, and none of my business, besides.

This morning I had another Mandarin lesson and am becoming fascinated. Mandarin is like German in that many of its words are made up of meaningful elements, as in huǒchē ("fire-wagon," Mandarin) for "train," or Armbanduhr ("arm-ribbon-clock," German) for "watch." Today I was taught the way the Chinese have adapted the name Alexander: they write it Yàlìshāndà in the pinyin spelling ("Asia-experience-mountain-big" ... not that this makes much sense).

I like the Chinese versions of English names: Dawei (David) Lundun (London) Duōlúnduō (Toronto), Wòtàihuá (Ottawa).

I have fun remembering the phrases and word order by translating them literally into English. Thus, "What's your phone number?" may come out more like "Your electric words number is how much?" A cinema is an "electric shadow place." I asked how to say, "Please say that again!" —the Chinese phrase means "Please again come one time!". Similarly, "Please next day again come." If you want to say, "Please don't go!" it's "Please not want go!" and "Go and take a look," is "Go look-one-look."

A couple, a two-person family, is "two-mouth." Newly weds are "little two-mouth." One's son is a "second generation seed." Metaphorically, an only child can be described as something very precious: "bright pearl in palm."

blending an assortment of thoughts and experiences for my friends, relations and kindred spirit

By Alison Hobbs, blending a mixture of thoughts and experiences for friends, relations and kindred spirits.

Monday, November 29, 2010

Saturday, November 20, 2010

The young people of Afghanistan

When I was a schoolgirl I had an adventurous friend called Christine. Although we lost touch, I've been thinking about her lately. She has recently been working as head of mission for UNMIS in Sudan. She also lived in Afghanistan for eight years, on and off, working for Oxfam, and has published three books about that country, one of them in collaboration with Jolyon Leslie.

On November 10th I listened to a presentation given by Paulette Schatz, formerly of the UNDP (and now a Senior Program Development Advisor for World Vision) who from 2007 to 2008 also lived in Afghanistan, managing the Joint National Youth Programme. An impressive lady, all the more so as she came across as modest and unassuming.

When Paulette first arrived in Kabul she had no budget and only a tiny office. She did eventually acquire a pick-up truck, but it was dangerous commuting to her office in the city. "I was worth $75 if kidnapped. My driver was worth $10. We were instructed never to take the same route twice."

She gave us an interesting statistic: 50% of the population of Afghanistan is between the ages of 12 and 26. Numerous though they are, young Afghans get precious little chance to make any decisions because the responsibility for their lives is taken by their parents or the elders of their community; that is the tradition. They mostly live in dire poverty, too. "Poverty is the absence of options," said Paulette. Working with the Afghan Ministry of Youth Affairs she managed to persuade the authorities to establish a Youth Parliament that meets four times a year with representatives from each province, the girls coming to the meetings with chaperones (their mothers or their aunts).

"When I'm out there, we don't think in terms of development. We think of building relationships." For example, she deliberately attended weddings, not making critical comments about the way things were done, but observing, and joining in as a friend of the families. She was able to buy new clothes, made locally, for impoverished schoolgirls. On International Peace Day, when a donation of white paint was received, the girls in Kabul painted the walls of their school courtyards rather than the outside walls, because it would have been dangerous to make these schools conspicuous.

While living and working in Kabul, she wrote poetry, perhaps as a way of getting her thoughts in order. She read us one or two of these poems aloud, during her talk. In one, she was imagining the hope in the minds of Afghan schoolgirls:

Paulette brought two young Afghans to the annual Youth Assembly at the United Nations Headquarters in New York. Eight young people from that country were actually elected to attend, but the authorities were afraid some of them might take the opportunity to defect. (CIDA is reluctant to sponsor young Afghans to come to study at Canadian universities, for the same reason.) One of the two who did come to the Youth Assembly, and who has since become a parliamentary candidate in his own country, made a speech in New York asking the delegates from the other countries to "stand up for Afghanistan." Paulette, who was there, told us that the gathering spontaneously rose to its feet.

On November 10th I listened to a presentation given by Paulette Schatz, formerly of the UNDP (and now a Senior Program Development Advisor for World Vision) who from 2007 to 2008 also lived in Afghanistan, managing the Joint National Youth Programme. An impressive lady, all the more so as she came across as modest and unassuming.

When Paulette first arrived in Kabul she had no budget and only a tiny office. She did eventually acquire a pick-up truck, but it was dangerous commuting to her office in the city. "I was worth $75 if kidnapped. My driver was worth $10. We were instructed never to take the same route twice."

She gave us an interesting statistic: 50% of the population of Afghanistan is between the ages of 12 and 26. Numerous though they are, young Afghans get precious little chance to make any decisions because the responsibility for their lives is taken by their parents or the elders of their community; that is the tradition. They mostly live in dire poverty, too. "Poverty is the absence of options," said Paulette. Working with the Afghan Ministry of Youth Affairs she managed to persuade the authorities to establish a Youth Parliament that meets four times a year with representatives from each province, the girls coming to the meetings with chaperones (their mothers or their aunts).

"When I'm out there, we don't think in terms of development. We think of building relationships." For example, she deliberately attended weddings, not making critical comments about the way things were done, but observing, and joining in as a friend of the families. She was able to buy new clothes, made locally, for impoverished schoolgirls. On International Peace Day, when a donation of white paint was received, the girls in Kabul painted the walls of their school courtyards rather than the outside walls, because it would have been dangerous to make these schools conspicuous.

While living and working in Kabul, she wrote poetry, perhaps as a way of getting her thoughts in order. She read us one or two of these poems aloud, during her talk. In one, she was imagining the hope in the minds of Afghan schoolgirls:

... We are a wave of humanity,"I believe in these young people," she wrote. "They see beyond the shackles that they wear." She claims that there's a profound spirituality in Afghanistan, and that people are still revere the 13th century poet, Jalal ad-Dīn Muhammad Rumi.

We are moving ...

Paulette brought two young Afghans to the annual Youth Assembly at the United Nations Headquarters in New York. Eight young people from that country were actually elected to attend, but the authorities were afraid some of them might take the opportunity to defect. (CIDA is reluctant to sponsor young Afghans to come to study at Canadian universities, for the same reason.) One of the two who did come to the Youth Assembly, and who has since become a parliamentary candidate in his own country, made a speech in New York asking the delegates from the other countries to "stand up for Afghanistan." Paulette, who was there, told us that the gathering spontaneously rose to its feet.

Labels:

Afghanistan youth,

Chris Johnson,

Paulette Schatz,

UNDP

Friday, November 19, 2010

In rehearsal

Julian Kuerti and Johannes Moser were at the NAC yesterday morning, rehearsing for a Bach-Stravinsky-Dvorak concert.

Before the rehearsal began, Eric Friesen of the CBC gave Donors' Circle members an introduction. The concert was to start with Bach's Orchestral Suite Number 1 in C, he said, written in the French style, the opening movement conveying the grandeur and magnificence of a courtly celebration at Versailles. The rest of the suite had a lighter touch; Mr Friesen told us it was Bach's heart dancing. We were to listen out for the woodwind and indeed, when they played it, I noticed a lovely passage for the bassoon and four oboes.

Stravinsky's Firebird Suite is an arrangement of his first major ballet, composed in 1910. (Here's a video clip of Stravinsky in 1961, conducting the triumphant Finale himself!) The Firebird legend is a rather scary, pre-Christian, Slavic one, in which good defeats evil after a lot of trouble. Mr Friesen said that this sort of thing was still popular; look at the recent success of Avatar. Stravinsky got drunk on sound, rhythm and musical architecture, he added, but "you can't look for melodies in Stravinsky!" I nearly accosted Mr. Friesen in the foyer after the rehearsal to tell him I didn't agree. There were some remarkable melodies in it, I thought, like snippets of Russian folksong, especially on the clarinet and horn.

At the end of his introduction to the devotees of the NACO, Mr. Friesen made a comment about their mission to introduce the younger generations to classical music. He said, "We have to take the music to where the kids are, without assuming that they've got to be like us." There were some three-hundred school kids in the auditorium who weren't at all grabbed by the Bach, as I could tell by leaning over the balcony and watching them in the stalls below me punching one another and whispering to the people in the row behind or playing surreptitiously with their forbidden smart-phones, but most of them sat up and took notice when it came to the Stravinsky. Before he started to conduct, Julian Kuerti turned to the kids and asked, "Be honest, how many of you have never seen a symphony orchestra live on stage before?" Most hands went up, and he told them that this piece was a good example of orchestral music; indeed it was, for them, with a full brass and percussion section participating (4 Horns, 2 Trumpets, 3 Trombones, Tuba, Timpani, Bass Drum, Snare Drum, Tambourine, Cymbals, Triangle, Xylophone, Harp, Piano). The sudden change from the soft opening to fff for the "infernal dance" made all the kids jump and squeal, "Oh!" Most of them couldn't refrain from clapping spontaneously at the end of the Firebird rehearsal, though a few deliberately did refrain; it wouldn't have seemed cool.

It was a pity that all the kids had to leave during the rehearsal break; otherwise they'd have heard Dvorak's Cello Concerto afterwards.

"Now Dvorak," said Eric Friesen, "was a consummate melody writer! ... The slow movement is to die for!"

I learned a couple of things, that the composer had already tried his hand at a 'cello concerto at the age of 24 which he had never published. When he came to Brooklyn and happened to hear a 'cello concerto by his colleague at New York's National Conservatory, Victor Herbert, he changed his mind about the potential of the instrument and tried again. Apparently Dvorak's sister in law, the girl he'd loved before he married his wife (echoes of the Mozart story, here!) died while he was working on the Concerto and so he paid a tribute to her by incorporating the tune of a song she used to sing, "Laß' mich allein."

I like the march rhythm on the other 'cellos that starts the last movement. They don't draw their bows across the strings, they beat them like drums.

Both the soloist (Canadian on his mother's side) and the conductor are in their early thirties. Apparently there's "a wave of new conductors" coming out of Canada now, one of the reasons being that we donors to the NAC sponsor a "Conductors Program" in Ottawa, every summer. Julian Kuerti also has the distinct advantage of his mother having been a professional 'cellist and his father being the world-famous pianist, Anton Kuerti. Julian now conducts the Boston Symphony Orchestra, as the second-in-command under James Levine. Someone asked, why aren't there more women conductors? The answer according to Mr. Friesen seems to be that women aren't usually assertive enough. If a young conductor didn't come across to an established orchestra as supremely knowledgeable and confident, the orchestra, in rehearsal, would "tear her to pieces."

Before the rehearsal began, Eric Friesen of the CBC gave Donors' Circle members an introduction. The concert was to start with Bach's Orchestral Suite Number 1 in C, he said, written in the French style, the opening movement conveying the grandeur and magnificence of a courtly celebration at Versailles. The rest of the suite had a lighter touch; Mr Friesen told us it was Bach's heart dancing. We were to listen out for the woodwind and indeed, when they played it, I noticed a lovely passage for the bassoon and four oboes.

|

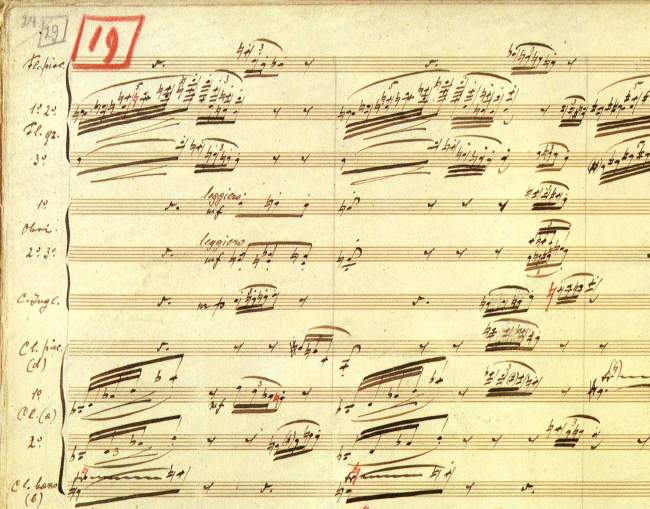

| A page from Stravinsky's manuscript |

At the end of his introduction to the devotees of the NACO, Mr. Friesen made a comment about their mission to introduce the younger generations to classical music. He said, "We have to take the music to where the kids are, without assuming that they've got to be like us." There were some three-hundred school kids in the auditorium who weren't at all grabbed by the Bach, as I could tell by leaning over the balcony and watching them in the stalls below me punching one another and whispering to the people in the row behind or playing surreptitiously with their forbidden smart-phones, but most of them sat up and took notice when it came to the Stravinsky. Before he started to conduct, Julian Kuerti turned to the kids and asked, "Be honest, how many of you have never seen a symphony orchestra live on stage before?" Most hands went up, and he told them that this piece was a good example of orchestral music; indeed it was, for them, with a full brass and percussion section participating (4 Horns, 2 Trumpets, 3 Trombones, Tuba, Timpani, Bass Drum, Snare Drum, Tambourine, Cymbals, Triangle, Xylophone, Harp, Piano). The sudden change from the soft opening to fff for the "infernal dance" made all the kids jump and squeal, "Oh!" Most of them couldn't refrain from clapping spontaneously at the end of the Firebird rehearsal, though a few deliberately did refrain; it wouldn't have seemed cool.

It was a pity that all the kids had to leave during the rehearsal break; otherwise they'd have heard Dvorak's Cello Concerto afterwards.

"Now Dvorak," said Eric Friesen, "was a consummate melody writer! ... The slow movement is to die for!"

I learned a couple of things, that the composer had already tried his hand at a 'cello concerto at the age of 24 which he had never published. When he came to Brooklyn and happened to hear a 'cello concerto by his colleague at New York's National Conservatory, Victor Herbert, he changed his mind about the potential of the instrument and tried again. Apparently Dvorak's sister in law, the girl he'd loved before he married his wife (echoes of the Mozart story, here!) died while he was working on the Concerto and so he paid a tribute to her by incorporating the tune of a song she used to sing, "Laß' mich allein."

I like the march rhythm on the other 'cellos that starts the last movement. They don't draw their bows across the strings, they beat them like drums.

Both the soloist (Canadian on his mother's side) and the conductor are in their early thirties. Apparently there's "a wave of new conductors" coming out of Canada now, one of the reasons being that we donors to the NAC sponsor a "Conductors Program" in Ottawa, every summer. Julian Kuerti also has the distinct advantage of his mother having been a professional 'cellist and his father being the world-famous pianist, Anton Kuerti. Julian now conducts the Boston Symphony Orchestra, as the second-in-command under James Levine. Someone asked, why aren't there more women conductors? The answer according to Mr. Friesen seems to be that women aren't usually assertive enough. If a young conductor didn't come across to an established orchestra as supremely knowledgeable and confident, the orchestra, in rehearsal, would "tear her to pieces."

Labels:

Bach Orchestral Suite No.1,

Dvorak 'Cello Concerto,

Eric Friesen,

Firebird Suite,

Julian Kuerti,

NAC,

NACO,

Stravinsky

Monday, November 15, 2010

Infectious hope

Instability is infectious, but so is hope.

|

| Inside the building |

Anyway, one thing at a time.

The Aga Khan Development Network in Afghanistan joins forces with government agencies to stimulate and support the economy. This includes the financing of new infrastructure (hydro-electricity projects, bridges, clean water, proper sanitation) and of innovative agricultural programmes and education, particularly in remote parts of the country, as well as the offer of microloans. The First Microfinance Bank (FMFB) kick-starts small businesses with these loans, buying the beneficiaries—often women, seeking to supplement their family income—such essentials as flour and wood for a bread oven, or a sewing machine. "Loan officers" then pay regular visits to see how the new enterprise is going and to offer advice. The AKDN has established hundreds of savings groups in northern Afghanistan that serve a similar purpose.

|

| Bridge at Darwaz (photo of a photo) |

|

| Afghans in council (photo of a photo) |

There are two more agencies in Afghanistan worth mentioning, the Aga Khan Health Services (AKHS) and the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC). The former makes the needs of women and children a priority, helping to train midwives, usually young women from remote areas, at Faizabad. This initiative has reduced child mortality by 85% in some parts of the country, and in Darwaz, in the north, a health clinic has been established with a staff of three doctors, serving 20,000 patients a year, some of whom travel for hours, for days, even, for their treatments or consultations.

The Aga Khan also takes Afghanistan's cultural needs very seriously, believing that "culture injects hope" into a deprived, traumatised community, or city, or nation. The AKTC uses its funds for the restoration of national monuments, for literacy and vocational training (in traditional weaving, for instance), for the arts and for the creation of parks and gardens. A few years ago, Canada's Governor General, Adrienne Clarkson, visited Kabul and was deeply impressed by the 16th century garden restored by the AKTC. She mentioned it in the speech she made at the Foundation Ceremony for the Delegation of the Ismaili Imamat:

...in only a year, the Foundation had transformed a dusty ruin surrounded by broken walls into a beautiful terraced garden with reconstructed adobe enclosures and the first of a series of fountains. It was astonishing. Nothing could more eloquently express the mission of your Foundation—to improve the material lot of the world's most devastated regions and peoples, yes, but also to respect spiritual and aesthetic considerations. Babur's Gardens serve as a point of hope and illumination for everyone who cares about Afghanistan ...

Labels:

Afghanistan,

Aga Khan,

AKDN,

AKFC,

AKHS,

AKTC,

Babur's Gardens,

Darwaz,

Delegation of the Ismaili Imamat,

FMFB,

Kabul,

microfinance,

University Women Helping Afghan Women

Sunday, November 7, 2010

The Peace Poppy

Tomorrow I resume my 2-hour Chinese lessons with the Ottawa Chinese Language Learning Centre; having left off at Lesson 5, my tutor promises that ..."we will learn Lesson 6 tomorrow after a quick review."

My mother when she was with me last month heard me trying to enunciate phrases like that, and it reminded her of the early 1940s and her cousin Douglas who in those days was likewise trying to learn Chinese, before being posted to the Far East.

"We used to dissolve into helpless giggles when he tried to make those funny noises!" she remembered.

Douglas Hardy was a twenty year-old Conscientious Objector, whose sincerity had made such an impression on the tribunal who examined his pacifist motives that he was given an unconditional discharge from military service. In spite of this exemption he opted to join the Friends' Ambulance Unit, in order to serve his country in that way. Douglas set off with the FAU for India, Burma and China and my mother and the rest of the family never saw him again. He died of typhus in 1942.

My cousin Wendy has done some research on this story, to which there's a reference here.

Douglas' parents never recovered from their grief (he was their only child). I met his mother, Lil, a couple of times and still have a poetry book she once gave me.

This year in Ottawa, there's a fuss in the media over the wearing of white poppies in memory of Conscientious Objectors and in memory of civilians who like the soldiers, sailors and airmen, have also suffered and died in wartime. Some people disapprove of the white poppy; some don't.

This blogpost was the starting point for a letter to the Ottawa Citizen, published in that paper on November 11th, 2010.

nǐ jǐdiǎn kāishǐ shàngkè? — jiǔ diǎn bàn.

|

| Douglas Hardy |

"We used to dissolve into helpless giggles when he tried to make those funny noises!" she remembered.

Douglas Hardy was a twenty year-old Conscientious Objector, whose sincerity had made such an impression on the tribunal who examined his pacifist motives that he was given an unconditional discharge from military service. In spite of this exemption he opted to join the Friends' Ambulance Unit, in order to serve his country in that way. Douglas set off with the FAU for India, Burma and China and my mother and the rest of the family never saw him again. He died of typhus in 1942.

My cousin Wendy has done some research on this story, to which there's a reference here.

Douglas' parents never recovered from their grief (he was their only child). I met his mother, Lil, a couple of times and still have a poetry book she once gave me.

This year in Ottawa, there's a fuss in the media over the wearing of white poppies in memory of Conscientious Objectors and in memory of civilians who like the soldiers, sailors and airmen, have also suffered and died in wartime. Some people disapprove of the white poppy; some don't.

*****

Labels:

conscientious objectors,

Douglas Hardy,

Friends Ambulance Unit,

Ottawa Citizen,

red poppy,

Remembrance,

white poppy

Saturday, November 6, 2010

Listening to Mrs Mozart

Diana Gilchrist and her husband Shelley Katz performed at a private house last month. Wearing a curly wig and a high-waisted, early nineteenth century dress, she was "Mrs. Mozart" for the evening and he played the ghost of the great man himself, accompanying her at the piano.

Diana Gilchrist and her husband Shelley Katz performed at a private house last month. Wearing a curly wig and a high-waisted, early nineteenth century dress, she was "Mrs. Mozart" for the evening and he played the ghost of the great man himself, accompanying her at the piano.

Pretending to relive her life with Mozart, the pianist in the background playing one of his sonatas as if in her imagination, she read from her "journal" sitting at a small table set with an antique cup and saucer before getting up to sing Abendempfindung, in which the listener's flowing tears are supposed to become the pearls in her crown(!) It is a song of some length and the breathing for it is challenging—I know the long phrases of this one. It was brave of Ms Gilchrist to make this the first item on her programme.

Pretending to relive her life with Mozart, the pianist in the background playing one of his sonatas as if in her imagination, she read from her "journal" sitting at a small table set with an antique cup and saucer before getting up to sing Abendempfindung, in which the listener's flowing tears are supposed to become the pearls in her crown(!) It is a song of some length and the breathing for it is challenging—I know the long phrases of this one. It was brave of Ms Gilchrist to make this the first item on her programme.Going back to her chronicle and having reminisced about Mozart's attraction to her elder sister Aloysia, a professional singer at the Viennese court, "Mrs Mozart" then demonstrated the Aria from the C minor mass, Et incarnatus est (click here for a lovely rendition of it by the French soprano Annick Massis), which Mozart had written for her, Constanze, after their marriage. Furthermore, his opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail has a character called Constanze in it, who sings the recitative and aria, Welcher Wechsel herrscht in meiner Seele. We heard this next.

Too much vibrato in this soprano voice for my taste, although Ms. Gilchrist did try to hold the resonance back to suit the confines of the small space we sat in, but when she performed the coloratura Queen of the Night's aria from the second act of The Magic Flute, Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herze, she was absolutely magnificent, perfect tone, great acting and all the notes! It was probably the best performance of this aria we've ever heard.

The concert finished with Vorrei spiegarvi, o Dio, another stand-alone aria, very Romantic in a 19th century sense (ahead of its time), and climaxing on an incredibly high note, a top G, I think. She hit it flawlessly.

Friday, November 5, 2010

Visible utterances

In the courtyard outside Jack's apartment block last night, after Chris and I had come down from his singing lesson, we lingered, despite the chilly, damp weather, to watch a short film that was being shown on a large outdoor screen. It was a recording made in 2008 of an event in Mexico City, remembering the Tlatelolco Plaza massacre of 1968. A giant megaphone had been set up in the same location, citizens of Mexico City being invited to speak into it and voice their thoughts and feelings about the massacre and about Mexican social justice in general. As each person spoke, his or her voice—and sometimes it was the voice of a child, sometimes an elderly person, sometimes a student of today, the same age as the victims forty years ago—was made visible, as it were, by beams of light bouncing up into the night sky to the rhythm of that person's words. The film (with subtitles in English) was entitled Vox Alta which means "aloud" or "in a loud voice." "Alta" also means "high" and The Mexican-Canadian electronic artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer was commissioned to create this work.

I thought of it again when I opened a recent edition of the London Review of Books that arrived in yesterday's mail and read a poem by Jorie Graham, The Bird on My Railing. The last quarter or so of the poem's lines are a description of a bird singing on a cold morning, so cold that you can see its breath:

It is also a poem about transience, loss, guilt and tenderness.

I thought of it again when I opened a recent edition of the London Review of Books that arrived in yesterday's mail and read a poem by Jorie Graham, The Bird on My Railing. The last quarter or so of the poem's lines are a description of a bird singing on a cold morning, so cold that you can see its breath:

when it opens itsShe calls this a "secret gift [...] of which few in a life are given."

yellow beak in the glint-sun to

let out song, it

lets out the note on a plume of

steam,

lets out the

visible heat of its

inwardness

It is also a poem about transience, loss, guilt and tenderness.

Tuesday, November 2, 2010

Battening down the hatches

|

| House behind the trees on Ojai Road |

"The severity of the climate [...] compelled them to batten down and caulk their abiding place." (John Badcock, Domestic Amusements, 1823)Who is this John Badcock, and was he related to the fellow who wrote this rather good (undated) provocative essay about liberty and loyalty, maybe a century later, which I have just discovered on the Internet?

Anyhow, mustn't digress. 7 cm snow fell Saturday night while we were being treated to a Persian meal in (on?) the Silk Road, invited there unexpectedly by Nicola and Maha. It was scrumptious: spiced soup and meats (qormas, kabobs) served with Afghan naan bread, Iranian ice cream with pistachios for dessert and to end the meal I drank a glass of green tea flavoured with cardamom. I've been brewing pots of this at home since, good for me, I'm sure. Afterwards, over a nightcap at our house, we discovered that Nicola, in a former existence at the Universidad de León in Spain, had published papers about the 4000 year old Gilgamesh epic in the Journal of Near Eastern Studies. I am reading one of these papers now.

|

| Chris and Laurie defeated by the Prius wheelnuts |

|

| Four "Roofmasters" start to work on our roof |

Labels:

John Badcock,

Nicola Vulpe,

Roofmaster,

Silk Road Kabob House

Monday, November 1, 2010

"Les Justes"

Camus, quoted:

It's exhausting to have to concentrate on a foreign language for two-and-a-half hours non-stop, but the actors' French, being Parisian, meticulously enunciated, with an artificial slowness, allowed no one to miss a point. The current French Theatre director at the NAC, Wajdi Mouawad, whom I admire very much for his stand against conventional thinking at the NAC and for his courage in confronting the nastiest politics of the modern world without flinching in his own plays, acted the part of one of the terrorists portrayed in Les Justes, the most intransigent one, in fact. The other actors were from France, the most interesting to watch being Émmanuelle Béart. She had a severe character to play here and a severe haircut to match, but still looked as vulnerably beautiful as in the films she starred in, Manon des Sources and Un Coeur en Hiver. Once again, as in the latter film, I heard her say with furious, growling intensity,

The Camus play is a sort of Socratic discussion of whether and why ends might sometimes justify means, in the struggle against hopelessly unjust régimes. It is set at the start of the twentieth century, in Russia. Is it right to assassinate a Grand Duke as a gesture against despotism? Camus' four just men and one just woman believe so, some more assuredly than others. The "poet" among them is all in favour and about to throw the fatal hand-grenade when he sees (in Act II) that the Grand Duke is accompanied by his wife and children. That is when the questions start:

The consequence of seeing this play is that it makes you realise that terrorists are human. All of a sudden your attitude to the world is not as straightforwardly black and white any more. You are forced to reconsider.

N'attendez pas le Jugement dernier. Il a lieu tous les jours.

Il y a dans les hommes plus de choses à admirer que de choses à mépriser.

Je ne connais qu'un seul devoir, et c'est celui d'aimer.

Il faut créer le bonheur pour protester contre l'univers du malheur.

Au milieu de l'hiver, j'ai découvert en moi un invincible été.I'm still thinking about the NAC production of Camus' Les Justes that I watched about a month ago, its message less optimistic than in some of those famous—wonderful!—lines selected above, from other works by that writer.

|

| Émmanuelle Béart as Dora in Les Justes |

Il faut aller jusqu'au bout!but in the Camus play that line was spoken in a political, not a sexual context. I was once again bowled over.

The Camus play is a sort of Socratic discussion of whether and why ends might sometimes justify means, in the struggle against hopelessly unjust régimes. It is set at the start of the twentieth century, in Russia. Is it right to assassinate a Grand Duke as a gesture against despotism? Camus' four just men and one just woman believe so, some more assuredly than others. The "poet" among them is all in favour and about to throw the fatal hand-grenade when he sees (in Act II) that the Grand Duke is accompanied by his wife and children. That is when the questions start:

I could not predict this...Children, those children especially. Have you ever looked at little kids? That serious look they have sometimes...I couldn't stand that look...A minute before, however, in the corner of the little square, I was happy. When the lamps of the carriage started to shine in the distance, my heart was thumping with joy, I swear it. It beat harder and harder as the carriage rolling got louder. It made so much noise inside me. I think I was laughing. And I was saying, "yes, yes." Do you understand? I ran toward the carriage. Then I saw them. They weren't laughing. They held themselves all straight and looked out at nothing. They looked so sad! Lost in their parade poses, hands folded, the doors on either side. I didn't see the Grand Duchess; I only saw them. If they had looked at me, I think I would have thrown the bomb. To at least put out that sad look. But they looked straight ahead.I don't know what happened. My arms got weak. My legs shook. One second after that, it was too late. (Silence. He looks at the floor.)Camus himself was torn over these questions. He was too intimately involved with the France-Algeria conflict to set his play in either of those countries, and the deliberate, Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt of using distant Russia as his setting is reinforced in this production by a symbolically stark, abstract set and very little physical movement on stage.

The consequence of seeing this play is that it makes you realise that terrorists are human. All of a sudden your attitude to the world is not as straightforwardly black and white any more. You are forced to reconsider.

Labels:

Camus,

Émmanuelle Béart,

Les Justes,

NAC,

Wajdi Mouawad

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)