I watched three brilliant teachers this week. What they had in common was self-assurance and a passion to share the ideas that drive them.

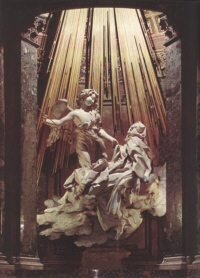

As I said I would, I went back to the National Gallery to watch the documentary film about Bernini, actually Part 2 of the BBC Series Simon Schama's Power of Art, entitled Bernini. In this production Schama presents a dramatised version of Bernini's life story, and shows us "the most daring sculpture in the history of art," the Ecstasy of St. Theresa. He talked about its "rippling cushions of stone," how the nun's habit, sculpted in this way, represents what's happening inside her: "a helpless dissolution into liquid bliss"—!

As I said I would, I went back to the National Gallery to watch the documentary film about Bernini, actually Part 2 of the BBC Series Simon Schama's Power of Art, entitled Bernini. In this production Schama presents a dramatised version of Bernini's life story, and shows us "the most daring sculpture in the history of art," the Ecstasy of St. Theresa. He talked about its "rippling cushions of stone," how the nun's habit, sculpted in this way, represents what's happening inside her: "a helpless dissolution into liquid bliss"—!

Schama doesn't pull any punches. Forget the euphemisms, he says, this is the face of sexual euphoria. Theresa was one of the barefoot Carmelites, says the narrator, depicted here, in "molten marble," not as a forty-something old maid, but as an unforgettably beautiful young woman. The artist, adept at "startling the people that mattered," shows spiritual ecstasy as something anyone can relate to:

What Bernini's managed to make tangible is something that we all, if we're honest, know we hunger for, but before which we're properly tongue-tied [...] No wonder when art historians look at this sculpture they tie themselves in knots to avoid saying the obvious, that is, that we're looking at the most intense convulsive drama of the body that any of us experience.

It is not a furtive piece, says Schama. Bernini "wants us to look, and look hard," witness the "audience" that he's incorporated into the ensemble (the faces painted on either side). He has set it up as theatre (apparently Bernini was also known as a playwright, painter and master builder) with "fake lighting", even. On the floor there's evidence that the earth has literally moved for St. Theresa, as there are the dead, arising from their graves. Bernini was not being "crude" however, understanding that for mystics, soul and body are one and the same. The Pope himself—Innocent X—liked it.

My second exposure to good teaching was when my daughter sent me a link to a presentation by Sir Ken Robinson, on the TED website, asking: Do schools kill creativity?, done as a sort of stand-up comedy that has the audience laughing out loud ... and thinking. He's highly provocative. Senior academics, he says, "look upon their body as a form of transport for their heads. It's a way of getting their head to meetings." Yet the modern education system puts this sort of people at the top of the intelligence tree, and treats the creative ones (musicians, artists, dancers) as less worthy of notice. Robinson tells the story of Gillian Lynne, choreographer, who was considered educationally subnormal, until a doctor realised that her lack of attention in school was a symptom not of deficiency but of her natural creativity. "Gillian isn't sick, she's a dancer..."

The third fine teacher this week was Barack Obama, whose Inauguration speech, if you ask me, was a lesson (not just to Americans) on how to think. I was taking notes!—noting that he mentioned the value of curiosity (hooray!) and of restoring Science "to its rightful place." As for national and international security:

Power alone cannot protect us, nor does it entitle us to do as we please ... Our security emanates from [...] the tempering qualities of humility and restraint ... We know that our patchwork heritage is a strength, not a weakness ... People will judge you on what you can build, not what you destroy ... we will extend a hand if you are willing to unclench your fist...

I was impressed by a story that came out in the Guardian about rather less famous Joe Favreau (27) who helps Obama to compose his speeches, working on the word-crafting in coffee shops for hours on end.

I can relate to that.

No comments:

Post a Comment