Julian Kuerti and

Johannes Moser were at the NAC yesterday morning, rehearsing for a Bach-Stravinsky-Dvorak concert.

Before the rehearsal began,

Eric Friesen of the CBC gave

Donors' Circle members an introduction. The concert was to start with Bach's

Orchestral Suite Number 1 in C, he said, written in the French style, the opening movement conveying the grandeur and magnificence of a courtly celebration at Versailles. The rest of the suite had a lighter touch; Mr Friesen told us it was Bach's heart dancing. We were to listen out for the woodwind and indeed, when they played it, I noticed a lovely passage for the bassoon and four oboes.

|

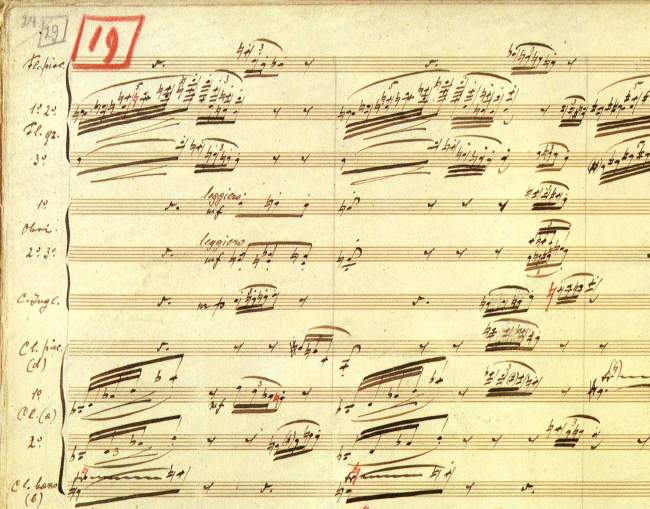

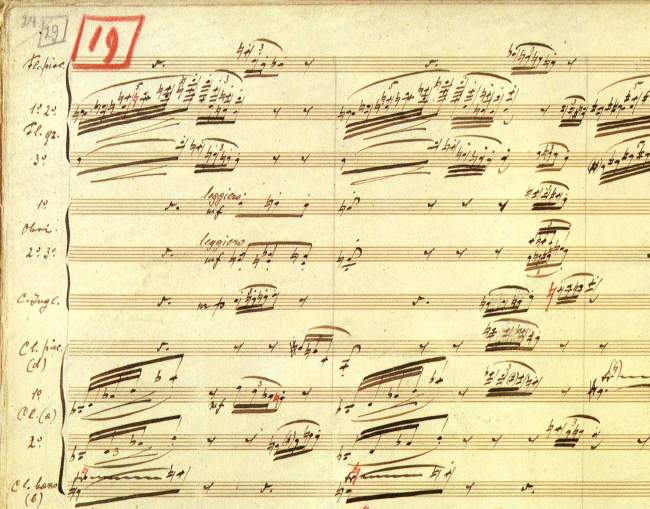

| A page from Stravinsky's manuscript |

Stravinsky's

Firebird Suite is an arrangement of his first major ballet, composed in 1910. (

Here's a video clip of Stravinsky in 1961, conducting the triumphant Finale himself!) The Firebird legend is a rather scary, pre-Christian, Slavic one, in which good defeats evil after a lot of trouble. Mr Friesen said that this sort of thing was still popular; look at the recent success of

Avatar. Stravinsky got drunk on sound, rhythm and musical architecture, he added, but "you can't look for melodies in Stravinsky!" I nearly accosted Mr. Friesen in the foyer after the rehearsal to tell him I didn't agree. There were some remarkable melodies in it, I thought, like snippets of Russian folksong, especially on the clarinet and

horn.

At the end of his introduction to the devotees of the NACO, Mr. Friesen made a comment about their mission to introduce the younger generations to classical music. He said, "We have to take the music to where the kids are, without assuming that they've got to be like us." There were some three-hundred school kids in the auditorium who weren't at all grabbed by the Bach, as I could tell by leaning over the balcony and watching them in the stalls below me punching one another and whispering to the people in the row behind or playing surreptitiously with their forbidden smart-phones, but most of them sat up and took notice when it came to the Stravinsky. Before he started to conduct, Julian Kuerti turned to the kids and asked, "Be honest, how many of you have never seen a symphony orchestra live on stage before?" Most hands went up, and he told them that this piece was a good example of orchestral music; indeed it was, for them, with a full brass and percussion section participating (4 Horns, 2 Trumpets, 3 Trombones, Tuba, Timpani, Bass Drum, Snare Drum, Tambourine, Cymbals, Triangle, Xylophone, Harp, Piano). The sudden change from the soft opening to fff for the "

infernal dance" made all the kids jump and squeal, "Oh!" Most of them couldn't refrain from clapping spontaneously at the end of the

Firebird rehearsal, though a few deliberately did refrain; it wouldn't have seemed cool.

It was a pity that all the kids had to leave during the rehearsal break; otherwise they'd have heard Dvorak's

Cello Concerto afterwards.

"Now Dvorak," said Eric Friesen, "was a consummate melody writer! ... The slow movement is to die for!"

I learned a couple of things, that the composer had already tried his hand at a 'cello concerto at the age of 24 which he had never published. When he came to Brooklyn and happened to hear a 'cello concerto by his colleague at New York's

National Conservatory,

Victor Herbert, he changed his mind about the potential of the instrument and tried again. Apparently Dvorak's sister in law, the girl he'd loved before he married his wife (echoes of the

Mozart story, here!) died while he was working on the Concerto and so he paid a tribute to her by incorporating the tune of a song she used to sing, "

Laß' mich allein."

I like the march rhythm on the other 'cellos that

starts the last movement. They don't draw their bows across the strings, they beat them like drums.

Both the soloist (Canadian on his mother's side) and the conductor are in their early thirties. Apparently there's "a wave of new conductors" coming out of Canada now, one of the reasons being that we donors to the NAC sponsor a "

Conductors Program" in Ottawa, every summer. Julian Kuerti also has the distinct advantage of his mother having been a professional 'cellist and his father being the world-famous pianist,

Anton Kuerti. Julian now conducts the Boston Symphony Orchestra, as the second-in-command under

James Levine. Someone asked, why aren't there more women conductors? The answer according to Mr. Friesen seems to be that women aren't usually assertive enough. If a young conductor didn't come across to an established orchestra as supremely knowledgeable and confident, the orchestra, in rehearsal, would "tear her to pieces."

.JPG)